Words into music…

Words into music…

In my last blog for this project I outlined some of the considerations a composer addresses when setting existing poetry.

Here, rather than being a full programme note at this stage, I write further about some of my compositional approaches in setting these incredible poems by Kathleen Raine (1908 – 2003) for my choral song cycle, Within The Living Eye. I reflect upon how my own harmonic language, ideas of metre and time signature, melodic and rhythmic devices, employment of word-painting and use of voices have all been utilised to shape a musical interpretation of these six poems. Hopefully this will give a little insight into the creative processes involved.

In seeking to get to the heart of Raine’s intentions, to illuminate musically her feelings and narratives about the landscape, it was necessary to discover which of her phrases and key words required some specific care and treatment. These moments might necessitate either a certain rhythmic gesture or inflection, something harmonically meaningful in the context of the movement, some particular melodic motif or even a mood shift to reveal a change in the mindset of the narrator of the poem.

It prompts the question: Is there a protagonist? Who is it that is narrating?

Whose voice was speaking in these poems? Like so many of Raine’s poems, written in the first person, the narrator does seem to be Raine herself, such is the depth of feeling she has for the landscape and the natural world, and her reverence for and communion with it.

Use of the choir

When there are large choral forces at your disposal, rather than solo vocal music with a single voice and instrumental accompaniment, there are choices, decisions to be made. When writing chorally, I regularly like to assign different sections of the text to different voice parts. I don’t always think of the piece as being melody with accompaniment, neither am I necessarily writing contrapuntally but thinking instead of the choir as having the potential for dialogue and interplay between voice parts, or it might be a lyric might be spread and shared through the parts through long phrases to the end of sections. This allows for a wider melodic range and allows each section of the choir to feel equally involved in relaying melody, harmony, key moments of the text. It’s an almost egalitarian feel.

In some moments within a poem, the importance of getting a message across might suggest voices in unison, or I might write purely harmonically; vertically, for the joy and immediacy of that homophonic texture. This makes the chords and harmonic changes more powerful if you have removed melodic and rhythmic intricacy for that moment; the focus is purely on the harmony in symbiosis with the text. I often think of the choral forces as having capabilities analogous to those of the orchestra. In looking at vocal ranges and blending of voices, there are textures, resonances, colour palettes to explore, for dramatic, rhetorical, emotional or lyrical effect. If a particular voice part is carrying both the text and the most prominent melodic feature, and one does not wish voices at unison or counterpoint but some harmonic focus is required, there are choices to be made. You may select key words from the text and play around with these, or have non-verbal sounds, sustained vowel sounds for example. Again, using voices ‘instrumentally’…

Interpreting the text musically – exploring a few pertinent corners…

Here, I shall not give a full programme note on all six movements but write with some detail giving insight into how certain passages were developed, how compositional decisions were made in order to facilitate the delivery of the text.

I – The Wilderness

Tonality

The opening poem seems dark and brooding, somewhat mournful. The tonality is therefore equally sombre: C minor, B flat minor, G flat minor. The opening line of the poem in the Alto part skirts around the tonal ‘centre’, settling on a B natural within C minor, the furthest away from being ‘home’, and certainly restless, unsettled. Things feel barren, lost, desolate and despairing. Yet there is a yearning to understand and be at one with the landscape, a thirst for knowledge of the earth (a key feature of Raine’s work).

Rhythm

The rising seconds with the semi-quaver dotted quaver figure seem to yearn for something. This ‘scotch snap’ rhythm possesses energy, starting with a very short note, driving forward that yearning feeling.

Word-setting

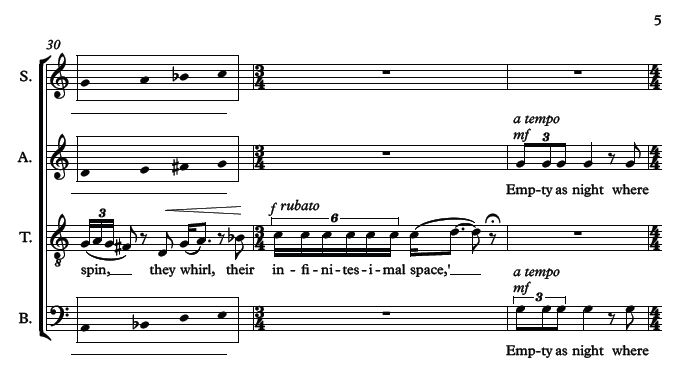

A later moment sees a brighter, more optimistic appearance of wells and water springing up, only to be seen draining away. Melisma, and falling, flowing phrases illustrate this (Sopranos and Altos bars 19-23).

Another yearning phrase appears, rising up in the Basses. But is the narrator reminiscing about being a child or instead feeling childlike, innocent, lacking in knowledge? Either way, using the Bass voice seems particularly poignant. ‘A child, I ran in the wind on a withered moor.’ The other voices sustain chords above, letting this key moment in the Basses have prominence. It goes on: ‘Crying out after those great presences who were not there.’ A falling fourth on the word ‘crying’. Historically, from John Dowland’s famous Lachrimae Pavans, to Roy Orbison’s tearjerker hit, composers have used to great effect a falling melodic motif to emphasise the falling of tears. Then a yearning, hopeful, rising scale turns back in on itself onto a darker, more remote chord…those longed-for presences indeed, ‘were not there’.

Again, channelling those voices from history: ‘Only the archaic forms themselves could tell’: this is in bare, open-fifths, akin to medieval plainchant where intervals were pure, most likely fourths and fifths and not yet tarnished with the daring third.

Using a surprising, optimistic major G flat chord ‘Yet I have glimpsed the bright mountain’ was a moment to use homophonic texture for directness, building up the chord downward in stages to bring a warmth of feeling to this section. Later, in a reversal of the striving, rising seconds in that ‘scotch snap/Strathspey’ rhythm from the opening, the ‘bitter berries red’ have their rhythmic figure falling. Again, it seemed to be in the major but falls to minor in a reminder of the earnest, serious moment of searching for some truth in the land.

II – At The Waterfall

After the dark, uncertain opening of the first movement, the mood here is deliberately lighter and, beginning with Sopranos and Altos, higher in pitch. The selection of this poem as the second in the cycle, helps bring that contrast because of its subject matter.

Imagery and Vocal effects

Some key words in Raine’s poem would seem to be: ‘empty’, ‘clear’, ‘silence’, ‘stillness’. For that ethereal, almost mystical, haunting yet feeling of purity, again, open fifths immediately resonate. If the harmony is too rich and full here, it will clutter what should feel as crisp and clear as that cool water.

Sometimes when imagery is so vivid in poetry, the trick is not to try to be too literal but to allow words and concepts to shape, inform and suggest musical texture and rhythmic/melodic activity.

The ‘gust of wind’ which follows is a good example. The use of the consonants, that guttural ‘g’ three times in in quick succession disrupts the tranquillity, it brings a sudden violence in the air. Using the word ‘sounds’ with its sibilant ‘s’ consonants also helps give the impression of wind billowing around.

III – Strange Evening

This feels like a typical Raine lovesong to the land, the sky, flowers and birds – our whole natural world. Again, it requires a change of mood; a warmer, more certain feeling as we discover just how passionately the land is revered.

Here, a vocal ostinato in a 5/4 time signature is employed, to give a context, a backdrop to the simple, heartfelt melody. Set, just as it might be spoken, the words end up with this unusual time signature. It hangs in space, almost static, with the element of conventional metre and rhythm put to one side to allow for long, lyrical lines which follow the words in intent. F major has often been used for pastoral scenes. The addition of close harmonies on seconds and thirds assists the tender, loving sentiment.

I wanted a simple, not forceful ending to depict the gentle, innocent marguerite (ox-eye daisy), hence closing on an unusual chord, ending the piece with a second inversion of the D major chord (the root is not at the bottom).

IV – Childhood Memory

This poem is at the heart of the song cycle and certainly embodies themes at the emotional crux of the piece: seeing things with joy and open-mindedness as would a child, rather than the cynicism and one-sided view of a jaded, dismissive adult, seeing things clinically, without emotion?

An aleatoric moment…

Again, rather than give a full programme note, I shall here discuss the use of aleatoric effects, that is, the element of chance and random selection, in one key passage.

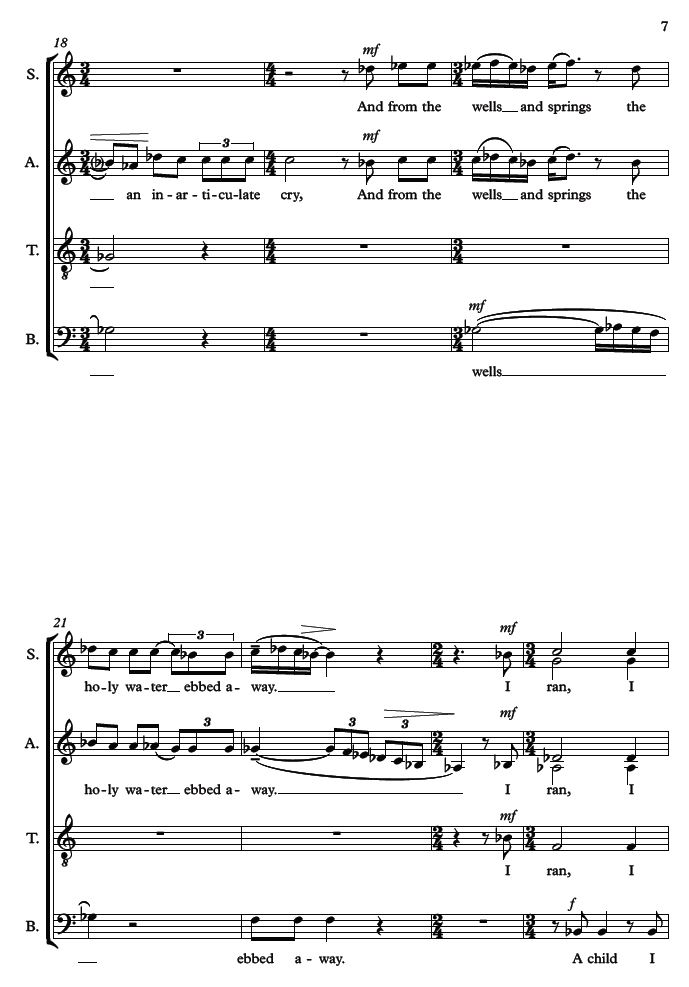

In this section:

‘You cannot gather those flowers,

The calyx in your hand is speed, is pow’r,

Is multitude in grain of golden dust

Smaller than point of needle, there they dance,

Unnumbered constellations as the stars

They spin, they whirl, their infinitesimal space,’

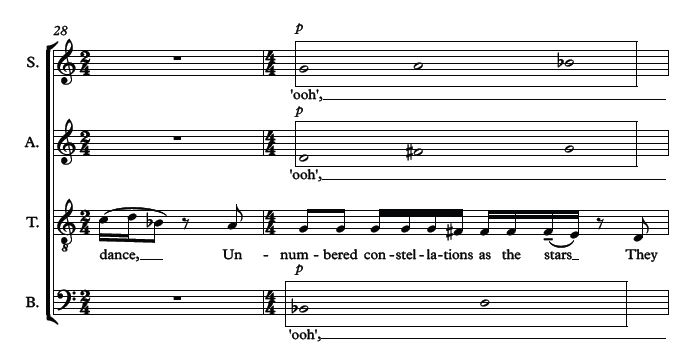

Bars 29 and 30 (shown left) have notes blocked out in boxes surrounding the stave. Only the Tenor part, which holds the melody and the text, has clearly-denoted rhythm and pitch; the other parts are written aleatorically. That is, singers have been assigned three or four specific pitches to be sung within these bars. They must sing only those pitches (selecting any or all) in the relevant bars, and no other pitches. Bringing that element of chance, singers individually may choose the order, duration, inflection at random, with rests, repetition as they so choose.

This creates a ‘wash’ of sound, sustaining the harmony of a G minor raised seventh chord with an added second, (and in the next bar you will see, spread between the parts all the pitches of the G minor melodic scale are allowed). This will bring an oscillating, constantly shifting texture which is an attractive device to employ in such a passage. Furthermore, no two performances of this section can, by their nature, be exactly the same, thus hopefully giving an adding frisson and feeling of spinning and whirling for those singing the words!

The vowel sound ‘ooh’ is the most effective here as it can be produced more quietly than other vowels and is neither too warm, nor too thin a sound to intrude upon the text.

Why this chord? The tension between the G and the F sharp and, later, between all the adjacent pitches in the melodic scale brings a mysterious, ethereal yet uncertain feel to this moment. The constantly shifting, elusive, slightly destabilising nature of a chord which never settles helps illuminate the spinning and whirling of constellations, in a way that is not too literal or obvious.

V – Spell Of Creation

After the first four movements, with their forlorn musings, mystical wonderment, tender devotion and childlike joy which battled world-weary cynicism, we have the sheer exuberance of the spectacle of creation, as depicted in Raine’s stunning poem Spell Of Creation.

She is at her finest here, vividly depicting a heady whirlwind of kaleidoscopic images, opening out from a tiny flower seed through tree, wood, fire, stone, iron, an O, an eye, sea, sky, sun, a bird of gold; these words collapsing in again on themselves, concertina-like, through heat, song, word, world, joy, grief, love, world, sun, fire, heart, bird, eye, earth, sea, sky, once more the O (of the Living Eye?) to distil back into the flower seed.

I previously set Raine’s poem The World – another tour de force of word-play and imagination, this poem also lending itself brilliantly to musical interpretation.

‘It burns in the void.

Nothing upholds it.

Still it travels.

Traveling the void

Upheld by burning

Nothing is still.

Burning it travels.

The void upholds it.

Still it is nothing.

Nothing it travels

A burning void

Upheld by stillness.’

Set for Soprano and Piano, one can see instantly how for a composer there was a fascinating prospect of creating a work in which each key word could be a specific pitch which then, in its reordering created almost by chance three different melodic lines, sharing a tonality but the harmonic context shifts and evolves. That is how I wrote The World, which remains a pivotal work.

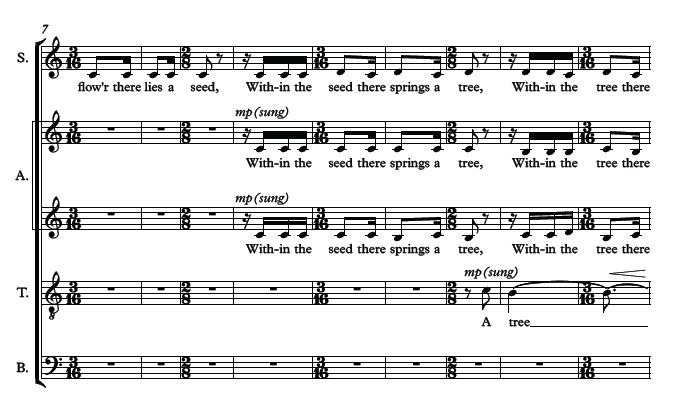

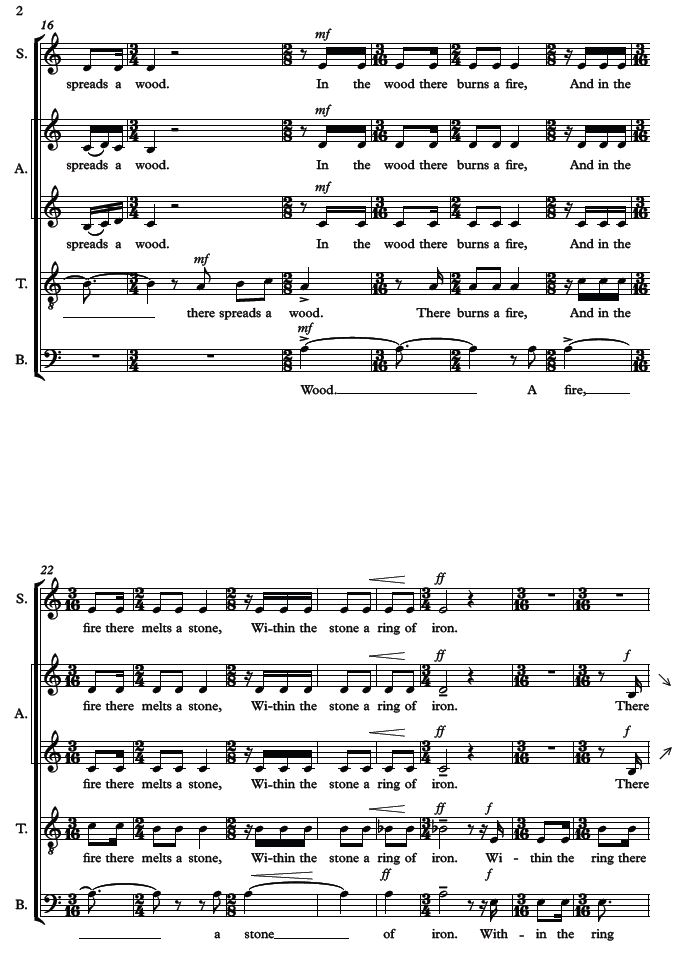

In Spell of Creation, there was an equally impressive and captivating structure in Raine’s work but my approach was different from in The World and that of the first four movements here. The seemingly incessant energy and dynamism of the text required a strong rhythmic impetus.

As with other vocal pieces of mine, I deviated briefly from the text, here borrowing key words to create a fast introductory whispered passage. From this: ‘Within the flower….’ etc., and the line ‘With blue unbounded of the living eye’ (from III – Strange Evening) comes my amalgamation of a title for the work, encapsulating that it is our eyes, living, awake, with the potential to notice…

Then, to create that feeling of opening out from the single source (the flower), the opening melodic line begins on a single note ‘C’ (‘Within the seed’), then opening out in contrary motion, between the voices into cluster chords of seconds, then thirds until the first five consecutive notes of the A minor scale are all heard together in bar 24.

Rhythmically, this was the most complex and exhilarating movement to write, in terms of notating and organising the intended structure and scansion. As in most of my vocal and choral settings, the text is set mostly in the rhythms in which it would be spoken.

For such large forces, one must be especially precise and accurate with rhythm and timings of words. Hence the use of multiple seemingly complex time signature changes which simply show where lie the emphases and phrase-ends.

If the singers think of these words as more or less being sung as they would be spoken, then it makes more sense and one need not grapple with the intricacies of 2/8, 3/16 etc. Quaver equals quaver, and so on. Curious note values are just for accuracy and explicitness of timing. Sometimes when one composes, so strong is the idea that it can feel really like musical dictation. You are simply writing down what it does; the words dictate the phrasing. That is what I meant by being a servant to the text and not getting in the way of what it wants to say. I like to translate literally the phrase ‘Qu’est-ce que c’est?’ (‘What is it that it is?’) What does the melody or rhythm want to do? Once you have begun to write, it has a life, it exists, it knows what it is and what it wants to do. Unless of course, you deliberately deviate and exploit its potential in other directions.

This movement is also notable for some key harmonic moments. The heralding of the ‘bird of gold’, in triumphant thirds in bar 55. The warmth of ‘And in the sun there burns a fire’ (bar 82-86) expressed through the bitonal richness of the six-note chord there, G and E major (plus A) melding together in an intoxicating manner. It was, as with this whole cycle, a joy to set these poems and to think of the wonderful, artful, dedicated singers who would be discovering, interpreting, performing the songs. There are many such moments in this movement, getting to the heart of Raine’s passion. I hope they resonate with the choir members!

VI – Say All Is Illusion

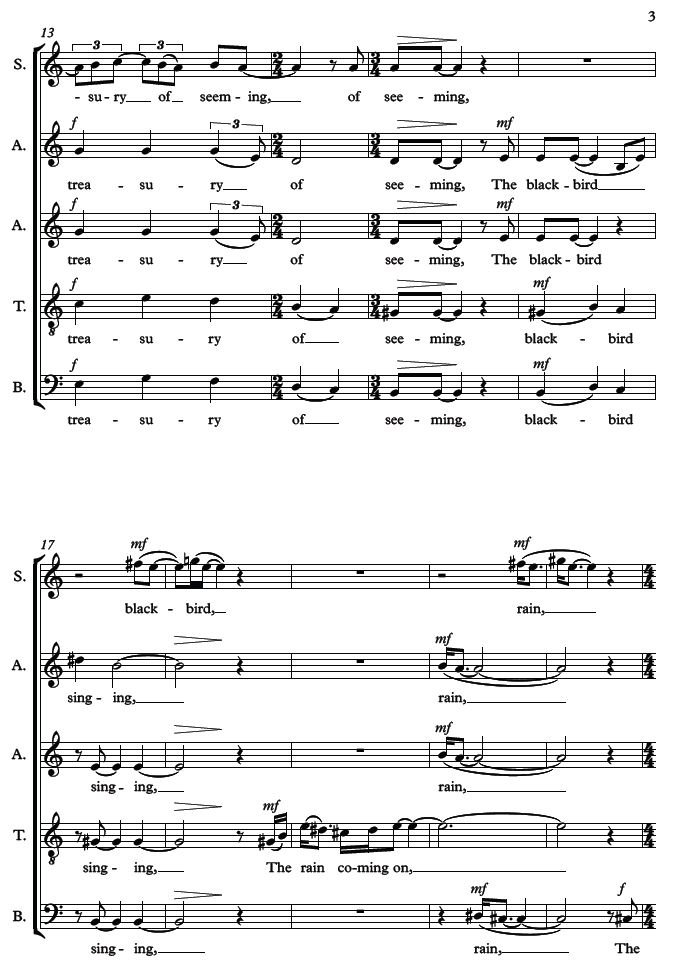

This final movement of the cycle, with the choice of this poem as a summation, a drawing together of the themes and ultimate revelation, the ‘inexhaustible treasury of seeming’, has several key moments which illustrate how thematic unity and common threads pull the cycle together.

An extended introductory passage builds on the earlier idea of yearning rising seconds, this time more hopeful. Secundal and quartal harmony (that based on 2nds and 4ths) is, as in other works of mine, prominent here. Voices in unison exclaim the opening lines, for heightened impact.

Deryck Cooke in his seminal work The Language of Music (OUP 1959) suggests there are three ways in which composers’ music can represent physical objects. By direct imitation, approximate imitation or by the suggestion or symbolization of a purely visual thing.

Here, it is the blackbird, whose unmistakable song cannot be precisely imitated but to whose notes there can be distinct allusion (Alto part bars 16-17), sings his song in an almost Charles Ives-ian Unanswered Question plea.

Repetition of rain, in the same way that the earlier gust of wind was called to mind creates an almost onomatopoeic feel, again with that scotch-snap rhythm, to convey movement, activity.

Almost in a synaesthetic way, ‘the leaves green’ in that bright, sharp key-feel brings the vivid colours to life. And how to convey a rainbow musically?! Remembering Cooke, one can but give a suggestion, convey or provoke a feeling akin to that produced by seeing.

Not quite the full harmonic series (concerning musical tone and frequency), as this is difficult to achieve with voices, but again, a merging of a C major 9th chord and a B flat augmented triad plus other notes, gives a vivid, full-spectrum feel to the word ‘rainbow’, in an attempt to bring to life Raine’s stunning imagery.

Afterword

There are many more moments on which I could have elaborated and would love to discuss another time with the singers. What is important now is to bring the insights of interpretation and joy of performance from the GSA Choir to all seven Composeher premieres. That is when the music comes to life and we gain so much inspiration from collaboration and innovation.

I hope readers found this blog insightful, particularly during the period of rehearsal. Wishing all involved in the project a happy, fulfilling time getting to know the music.

Copyright, Rebecca Rowe.