The harmonic journey…

The harmonic journey…

In my last blog, I recounted my discovery of a pioneering scientist and artist of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Maria Sibylla Merian. From her monumental folio Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, I excerpted five pieces of text for five miniature movements, each taken from a description of an illustration of insects in their various metamorphological stages and centred around the plants on which they lived. Merian’s language, and its English translation by Lannoo Publishing, has scientific detail, light-hearted whimsy, and poignant insight into the cycles of life. Now that I have my selected text(s), I must ask myself – how do I convey all of these different aspects in one ten-minute piece? What musical language should I use? How should I structure the piece so that we feel a progression of transformations and change, such as those Merian documented?

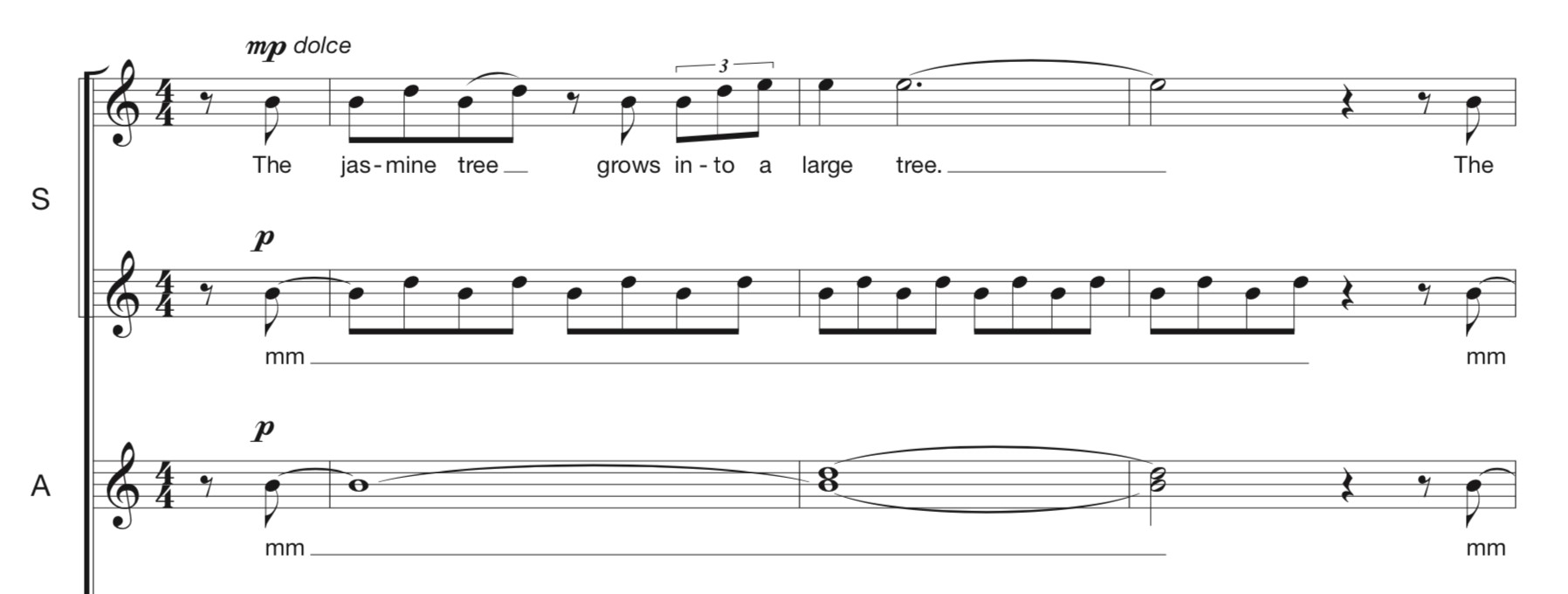

Here is an example of my excerpts of Merian’s writing, the text from the second movement of my piece, Jasmynboom (jasmine tree):

‘The jasmine tree grows into a large tree. The leaves are thick and juicy green. It yields thick and heavy flowers. If a branch is broken, a sap oozes out. They easily let themselves be multiplied.

‘The crowned caterpillar eats the foliage of this jasmine tree. On 20 September it changed. Such a lovely clouded butterfly emerged, with six white patches on the surface of each wing. No pen could describe its beauty.’

Right away, I know that this piece is going to be a little bit different from some of my others. I want a musical language which is earthy and elemental, but still light. I do not want to tie it down with heavy chord voicings or sustained harmonies, though I have used them with purpose in many other works of mine. I must focus on the minute details of each voice’s line to make this happen, ensuring that all parts have plenty of rhythmic activity and melodic motion throughout the vast majority of the piece. I thought a great deal about Francis Poulenc as an example of this, particularly his Quatre Motets pour le temps de Noël. I also want there to be cohesion and progression between the movements, but with each maintaining its own identity, as if the movements were each separate, distinct panels within one work of art.

In conceiving of my works, particularly my choral works, I usually tend to centre my thinking around texture and harmony. These elements will also play the most critical roles here. In terms of texture, one can easily imagine musical implications of both the visual subject matter of Merian’s art and the wording and turn of phrase of her descriptions – creeping insect legs, flapping wings, organic twists and turns of plant life. Texture is built out of rhythm, and lots of rhythmic activity, with plenty of independence between the voices, will create the impression of this abundance of life and movement.

However, before I dive into bringing that to life, I want to ensure that the piece will have cohesion and flow. For a piece of this length, I must plan some sort of harmonic scheme or journey to keep these delicate textural threads together. When we think of overarching harmonic structures in concert pieces, or when music students are taught about them at university, we often think of Germanic symphonies or sonatas of the nineteenth century with specific types of modulations and tonal moves, centring around the relationship between the I chord (first chord) and the V chord (fifth chord). However, there are infinitely more ways to create a harmonic journey for the listener beyond those that are reminiscent of what a nineteenth century European composer might do. How will I set up my plan? With the earthy, elemental topic of my work, what better place to start than one of the most basic units in music – the interval.

An interval is the relationship between two notes. It can be melodic or harmonic, or ‘simultaneous’ if you like. Chords are made up of multiple harmonic intervals at once. The qualities of the intervals within the chord – perfect, imperfect, consonant, dissonant – dictate what it will sound like to us and how it might make us feel. Intervals on their own have strong character or flavour as well. A minor second is the smallest interval we have in our tuning system, and a major seventh is the largest, just short of the octave (which, in turn, is exactly the same note played one register higher or lower).

If you are a musician this is likely old news to you; if you are not or you haven’t studied music in an institutional setting, it may sound like gibberish. That’s fine. If you enjoy choral music (which I can only assume that you do, if you’re reading this!), intervals are likely at the heart of why you love the pieces that you love, and you probably already know what some of them sound like. For instance, if you’re a choral singer, you may be a fan of Renaissance choral music by composers like Tomás Luis de Victoria, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, and Thomas Tallis. The ends of the long phrases resolve to very open harmonies, which are comprised of perfect fifths. ‘Perfect’ intervals are fifths, fourths and octaves; they have a wide-open sound and they cannot be major or minor. Perfect fifths and octaves are consonant, as opposed to dissonant, and therefore they sound like they don’t need to resolve. Perfect fourths often sound consonant to us as well, though they’re not quite as stable on their own. If you listen to Medieval or Renaissance choral music, you’ll hear a lot of these open sounds (particularly at cadences), and you’ll probably hear a lot of melodic perfect fifths too – think of the opening lines of Victoria’s O Magnum Mysterium or Tallis’s Salvator Mundi.

To illustrate this, here’s an even more stark example you may be familiar with – fourteenth century composer Guillaume de Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame, a major influence on my music:

That epic first moment of the Kyrie is two open fifths stacked on top of each other. Throughout the piece, we continue to hear tension and release within phrases centred around perfect fifths. The music sounds grounded and wide open.

Now, contrast this with Morten Lauridsen’s O Magnum Mysterium, likely another favourite for many of you:

If you listen to that first cadence, it sounds quite different to the conclusions of musical phrases in the Machaut. This chord is made up of sixths instead of fifths, which are ‘imperfect’ consonances – they don’t feel like they need to resolve, but they don’t feel as grounded as the fifths in the Machaut, and they can be either major or minor. Throughout the first sections of this piece, Lauridsen uses chords that are mostly based on thirds and sixths, not fifths. Those of us who have taken music theory classes would call these inverted chords – there is a note other than the root note of the chord (D in D major, F in F major, etc.) in the bass voice. All of these imperfect consonances and inverted chords make the music feel as if it is floating. It is consonant to our ears, but ethereal and untethered. The sound worlds of these two pieces largely arise out of the intervals the composers used.

As I said, I will use intervals to guide the overall harmonic journey of my piece and thread the different illustrations together. I will start by focussing on the smallest intervals in the first movement, then incrementally expanding the central interval with each successive movement. In combination with rhythms and textures reminiscent of the plant and insect life Merian depicted, I hope this will keep the piece cohesive while it shows growth and change from section to section.

The first movement, Ananas, starts with a fluttering, staccato rhythm on a major second, and grows from there:

In the second movement, this expands to focus on thirds and fourths, alongside a more sustained texture:

This expansion continues throughout the rest of the piece, both in terms of each sections’ melody and the larger harmonic relationships I use within each movement. For instance, the third movement, Carduus Spinosus, depicts worms and beetles that grow as they eat the root of thistle plants. With this darker perspective on symbiosis and the life cycle, I used F minor and B minor – an augmented fourth apart, one of the most dissonant intervals. The fourth movement, depicting hearty, high-flying butterflies that live on grapefruit trees, takes its dramatic, open sound and swift harmonic moves from perfect fifths.

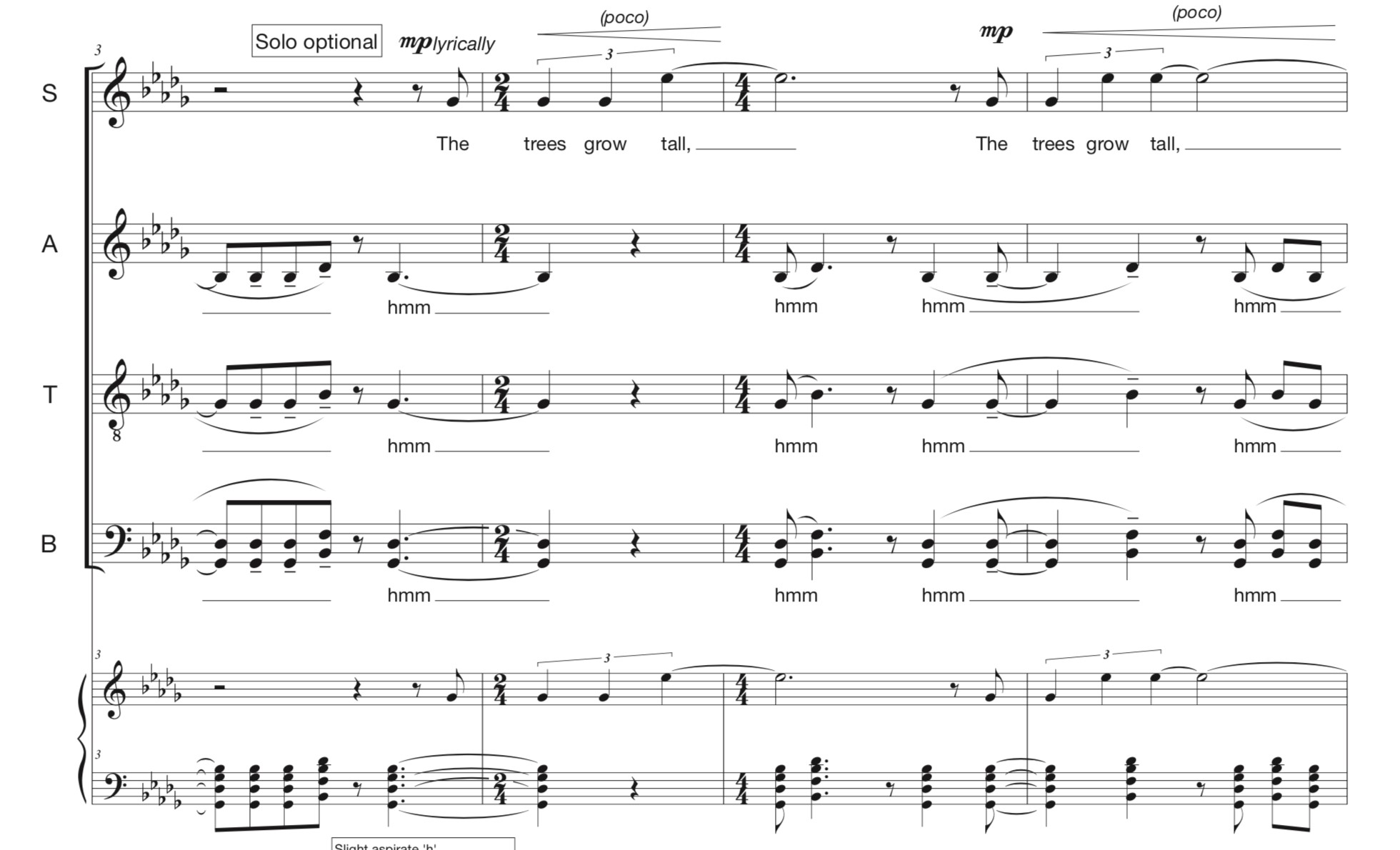

Cacau Boom is the final movement, depicting the cocoa trees that grow tall and thrive in the South American climate, but only if they start their lives in the shade of another tree for protection from the sun. The text is perfect for the wide melodic interval of a sixth:

The accompanying alto, tenor and bass voices hum an accompaniment that is rhythmically reminiscent of the opening of the first movement and other moments throughout the piece, but using chords instead of one note at a time, giving a much more expansive feel.

In conclusion, I have named the piece Papilionum, Latin for ‘butterflies’ or ‘of butterflies’. This pays homage to subject of the piece, the original (much longer) Latin name of Maria Sibylla Merian’s book, and her mission and legacy, first and foremost, as a scientist. I cannot wait to share Merian’s work and my piece with the GSA Choir, Jamie Sansbury, and all of you!